DELTA DOWNLOAD INTERVIEW

Stomping nuts with Bill Steber

He's been capturing Mississippi blues culture with his camera lens for nearly three decades. Bill Steber's images are evocative, provocative and memorable. They're also recognized worldwide. Here the acclaimed photographer, musician and artist takes on issues of race, culture, access and avocation.

It was 3 o'clock on a Wednesday afternoon and Bill Steber was still in his pajamas. This was no means typical. But his reason was legit, having just finished a slow Southern brunch with his wife when a ringing phone broke the mood.

For the next 90 minutes, Bill paced his yard in his sleepwear, "stomping nuts" from a pecan tree on his property in Murfreesboro, Tennessee...all the while absorbed in a spirited back-and-forth with Delta Download.

It was apparently a mutually fulfilling exchange, as when it wrapped, Bill had added 6,450 steps to his daily fitness goal, and I came away satiated with answers to deep-dive questions I'd pondered since first becoming aware of his work in 2006.

One falsehood Bill quickly put to rest is that he's senior citizen. I figured he had to be, because his acclaimed photos seem to be from an era long passed. Sort of like Dick Waterman, now 85, photographing Son House or John Hurt back in the 1960s. Bill was quick to put my very flawed misconception to rest. He's 54.

trajectory

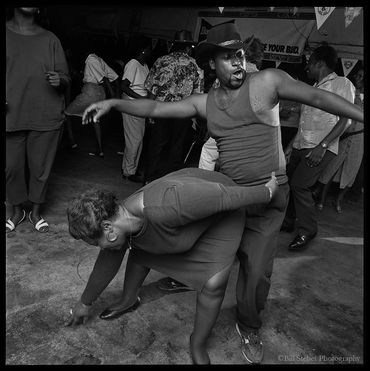

BILL STEBER IS A RENOWNED PHOTOGRAPHER WHO HAS DOCUMENTED BLUES CULTURE in Mississippi for the last three decades. His photos are intimate and immersive, as if the viewer can hear and smell and feel the essence of what he's so stunningly captured.

With his lens, Bill exposes the common, the hidden and obscure. His photos grant access to a world that feels foreign yet oddly familiar in its shared human experience.

With a body of work known worldwide, Bill's photos include blues musicians and juke jivers, churches and river baptisms, folk rituals and hoodoo practitioners, farming methods and prison inmates—each revealing uncommon traditions that birthed or shaped the blues.

Bill's life's trajectory was set in 1992, when he was just 27 and experienced the "single most transformative thing in my life, the drive, the Delta, everything."

It was a sculpted figure of dead woman lying in a wooden coffin. Being that it was life-size, the piece occupied significant space in the shotgun shack of its owner, James Henry "Son Ford" Thomas, an internationally-known Delta bluesman and folk artist whose sculptures reflect his work as a gravedigger.

delta blues man, folk ARTIST, gravedigger: son thomas in his leland shotgun shack, august 1992

video about Son Thomas

son thomas with bill steber in leland, ms, august 1992

happenstance

It was pure chance that brought Bill to Leland to meet Son and Pat Thomas (shown at left), one of Son's six children.

He was on assignment for The Tennessean to cover a recently completed parkway from Natchez to Nashville. Bill remembers that day in 1992 like it was yesterday, when he and a writer colleague drove out of Natchez, which was the second-largest slave market in the United States, trailing only New Orleans.

"The air in Natchez was heaviest, like it was hard to breathe. The humidity, heavy moss on trees, ghosts bumping around in the street. Then that deep heavy foliage opens up to fields—and you almost can breathe again."

Bill had never been to the Mississippi Delta, and figured they could eke out a day to explore. Better yet, his colleague happened to know the former director of Mississippi tourism, Malcom White, who owned Hal & Mal's in Jackson. The pair swung by the eatery, met with White, and came away with a list of phone numbers and addresses for some of the Delta's best bluesmen, some obscure, some not. That list brought him to Son Thomas.

As they continued road tripping north into the Delta, Bill remembers a visceral felling, like the music had hit the landscape, and the two were inextricably tied together.

"Emotionally, it was both a calm and excitement in the air, a kind of thrill, indefinable thrill, a wholeness and a calm. I felt grounded to a place," says Bill, a kid who grew up in very rural Tennessee and was the first generation to experience school integration in 1970.

"Suddenly all things made sense to me. I felt like this is my place. Every place has a certain energy, and that place vibrates in return. Whatever the wavelength, I'm locked in on that. I realized the culture created in the Mississippi Delta was wholly unique in American history."

Abbay & Leatherman in Robinsonville, one of the largest cotton plantations in Mississippi, and the boyhood home of blues icon Robert Johnson (1912-1938)

click each photo to enlarge

modus operandi

In 1993 Bill bought the soundtrack to Robert Mugge's Deep Blues and found a motherlode of Mississippi blues including R. L. Burnside. Lonnie Pitchford. Jessie Mae Hemphill. Big Jack Johnson. Junior Kimbrough...blues musicians who were still alive. And Bill felt compelled to seek them out.

His pursuit led him to Junior's Place, a juke joint isolated up in the hills near Holly Springs in a building formerly used as a church. The club was frequented by mostly local folks, but attracted visitors from around the world, including members of U2 and the Rolling Stones.

Operated by Junior Kimbrough, the juke was "a cathedral of art" that "became an increasingly religious place for me." The glitter, bright colors, pillars, the molding...it was spiritual, the closest thing to Fela Kuti's Shrine in Nigeria, one of the world's most sacred musical meccas.

There was an aura about Junior's that was trance-like. "The grinding, drinking, you could lose yourself. It was religious, a psychedelic experience."

Bill visited Junior's two dozen times from 1993 to 2000. I asked him about the first time, when he showed up alone, no photo assistant, just him and his gear. How was he able to infiltrate this personal and emotional space to capture intimate images amid flailing arms, riveting hips and faces fully absorbed in the deep blues vibe?

Bill willingly shared his modus operandi, starting with his first shoot at Junior Kimbrough's in 1993. About 4 pm on a Sunday, Bill pulled up in his gray Nissan Pathfinder loaded with camera gear. A couple of cars were parked out front.

Having scoped the place out in advance, Bill knew the crowds would begin arriving in earnest around 6 or 7 pm after church let out, folks coming to Junior's Place straight from services, dressed in their Sunday best.

"So I walk in before things start going and talk to the owner: 'My name is Bill Steber and I work for a paper up in Nashville. I came for the show tonight, okay?' Then I tell him here's what I'd like to do—no video, no audio, black and white photos only, a documentary thing. You have to be fully honest. I think people can read your intention, whether you're full of crap or not."

Next Bill brings in his gear including plenty of battery packs in case electricity was spotty or unavailable. "Logistically how I need to work is two lights and one camera. One light in the main room, pointed raking across the room. I shoot the band, switch off the one in the main room. Then I bounce the camera light off the ceiling." Meanwhile people get curious and ask, "Hey man, we gonna be in a magazine?"

So I ask the obvious question, the one about the observer effect...and if people end up performing for the camera?

"Oh yeah, the Heisenberg thing that what's being observed is change by the observation," Bill says dismissively. "It's going to happen, no matter what. That's why I become so intimately a part of it, just one amongst them, versus a surveillance camera."

Becoming part of the crowd may mean buying someone a beer, hanging out with groups of people, talking to the musicians. "I always hang back until that trust is present, that I'm not some fly-by-night coming in from a national magazine. Once that trust is there, instead of being ten feet away, I can be two feet away."

But what if the dance floor is crowded and Bill needs to get in the center of things to grab a shot?

"I go out there and dance. I was laughing and cutting up with this one guy about his shoes, and he said, 'What you know about shoes?' and I said, 'Nothin. You're gonna teach me. Hey, what are you drinking?' And I buy him a beer."

"They enjoy you enjoying them. People want validation. Instead of 'here's this dude with this camera exploiting me again,' I make it a validation of people. Sure, people are showing off, but it's giving everybody an excuse to be their best selves."

inspiration

One of Bill's favorite writers is Robert Gordon, who he says "writes like a photographer."

"You can smell the fish cooking and the sawdust on the floor. There's a granular feel of what's in the space. My main goal is to make the picture look like the music sounds."

Bill says there's always a soundtrack in his head when he's in the field—a synesthesia.

He can be shooting an old barn with vines climbing up it while hearing the crackle of an old 78 of Charley Patton in his head—"a visual echo" as he puts it, hearing colors and seeing sounds.

Bill draws inspiration from Herman Leonard's smoky images of jazz legends from the late 1940s and 1950s. His work is also inspired by so-called street documentary styles of Robert Frank, Garry Winogrand, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Eugene Richards and Bill Allard.

"Allard's book The Photographic Essay had a huge impact on me," Bill admits of the 1989 retrospective that spotlights Allard's focus on human emotion and going for the shot others wouldn't attempt, where lighting conditions are poor or settings are questionable.

Check out this short video, To Wander With No Purpose, featuring interviews and behind-the-scenes with William Allard, including what he looks for when photographing people.

The video includes Allard photographing in Mississippi, a shoot that Bill Steber accompanied him on. This special feature film was released on World Photo Day 2018.

time to go

Bill's intimate photos of Mississippi blues culture have provoked a seeming never-ending question about access—how in the world can he capture such provocative and evocative photos, each one telling a story of its own? His answer always seems to surprise.

"These people went out of their way to make me feel welcome," says Bill, adding he would develop prints of his photos and bring them along on his next trip to Mississippi. There he would share them with juke owners and patrons as a show of gratitude and respect. For Bill, it's not a big deal to go into a Black club and be accepted. It shouldn't be. Even if you're a white guy from out-of-town.

"Maybe it's the vibe you put out. But the generosity of people in Mississippi continues to deeply humble me."

Yet Bill admits that he doesn't always have carte blanche, and muses what would happen if the proverbial shoe was on the other foot regarding race and access.

"Can you imagine a Black photographer from Philadelphia going into an all-white shit kicker bar in East Texas? It would never happen without the photographer being put in the hospital on the first night."

Bill recalls one time when his "spidey senses" told him it's time to pack it up and call it a night.

"There was this place that only spun records—the Black Castle (shown above) on Greasy Street in Ruleville," Bill recalls. After getting the okay from the club's operator, Bill went to work capturing the patrons and atmosphere. A few hours later, the older folks left and a younger crowd took their place.

"I could just hear them thinking, 'Why's a white man in here?' They had no mental place to process it. Overall this feeling started. The vibe had changed, and I knew I wouldn't get anything more. It's like they were telling me, 'You've had your fun here. Now let's go back to being a Black club.'"

So Bill discretely packed it up and left. It wasn't about fear, nor should it be. It was about reading the room and respecting the vibe—something Bill's gotten pretty good at over the years.

Harmonica player Cleo Pullman plays at the Blue Front Cafe in Bentonia, MS. The oldest continuously-operating juke joint in Mississippi, the Blue Front is operated by Jimmy "Duck" Holmes, and was opened by his parents in 1948. This unassuming juke has gained international acclaim among fans as an easygoing, down-home blues venue.

reckoning and responsibility

Bill's work has brought him to a racial reckoning of sorts.

"I've learned more about my particular white privilege, partly racial but economic too. You can check off all the privilege boxes: I'm a white Anglo-Saxon middle-age white guy, someone who doesn't have a trust fund and went to public schools."

There's the existential questions: Who owns the culture? Who gets to interpret the culture?

"I wrack my brain and my heart over that. The idea of permissions. 'Who gives you permission to do this?' I've been reckoning with this from the very beginning, it's always in my thoughts."

Bill continues in this philosophical and relevant vein: "I have a deep responsibility as an interpreter of the culture. How do I handle that responsibility? There's Walker Evans' cool formalism which codifies the subject and composition emotionally. Then there's Eugene Richards, who's deeply engaged, highly interpretive, fearless emotionally, the most revelatory and expressive and interpretive in the world."

Just like Evans and Richards, Bill knows his work, in and of itself, will be interpreted and "slightly romanticized." To continue that work, Bill admits he has to overcome aspects of representation—the "what" and "how" he represents Mississippi blues culture in his photography.

"If I'm deeply honest with myself regarding my experience, it's borne of a deep love for the people, the culture, the landscape, the music. My hope is that this sincere love carries through toward a kind of honesty toward my limitation of having a deeper understanding about the culture I'm capturing. I can compensate for this, but I can never overcome it."

more on Bill Steber

bill steber on junior kimbrough's place

3-MIN VIEW: There's few places where local music impacted the local culture in ways vital and real. No place ever compared to Junior Kimbrough's, according to Bill Steber. In the compelling video, Bill shares why Junior's Place has never met its match.

award winning: bill steber and his work

explore

Bill Steber's photo website features not only a selection of his world-renowned images, but compelling backstories behind each photo. Bill is also an internationally known music researcher and writer.

exhibit

Bill Steber's work is featured in SOUTHBOUND: Photographs of and about the New South. This exhibition comprises 56 photographers’ visions of the South over the first decades of the twenty-first century. Also check out Bill's lecture and musical performance on SOUTHBOUND.

listen

Besides his photography, Bill Steber makes music with The Jake Leg Stompers, the Hoodoo Men and The Jericho Road Show. He has performed around the U.S. and in numerous countries including England, Scotland, Germany, Austria, Japan and India. Bill's YouTube Channel features more videos, including some of Delta blues legends.

check out

Bill Steber's video and more on Southern Blues and Photography for one of his many exhibitions, this one at The Arts Company in Nashville.

deep dive

In 2017 this in-depth Q&A with Bill Steber was featured in Acoustic, Folk and Country Blues. Also check out this deep-dive bio for more about Bill, his influences and work.

awards

Bill Steber is the 2011 recipient of the coveted “Keeping the Blues Alive” award presented by the Blues Foundation in Memphis, TN. His many achievements include a grant from the Alicia Patterson Foundation, an Ernst Haas Award and Morrie Camhi Award in documentary photography, as well as dozens of other national and regional photography awards.

Copyright © 2024. All Rights Reserved. No part of this site may be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission of the copyright owner.

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, you are consenting to the use of them for tracking website traffic.